Kenya says it is ready to lead a UN-backed mission to Haiti, but at home faces growing pressure to justify the risky intervention and the wisdom of sending its police to the violence-ravaged nation.

The United Nations Security Council on Monday approved a Kenyan-led security operation to the Caribbean nation, where the economy has collapsed and violent gangs control territory seized from a weak government.

The country’s beleaguered leaders appealed for a year for international help to restore order, but the memory of other failed interventions in Haiti kept volunteers at bay.

Then in July, a lifeline: Kenya said 1,000 of its police forces could take the lead, an offer welcomed by the United States and others that had ruled out putting their own boots on the ground.

With the UN’s greenlight, Kenyans awoke to the reality that their police could soon be fighting heavily armed gangsters in a strange and distant nation and started asking questions.

“What is their mission in Haiti?” asked Emiliano Kipkorir Tonui, a veteran peacekeeper who oversaw Kenyan deployments to Liberia, East Timor and the former Yugoslavia, among others.

“Kenyans must be informed. The leadership is answerable to the people,” the retired brigadier general told AFP.

– ‘God’s Will’ –

The government has been on a campaign blitz to defend the intervention, but is yet to take its proposal before parliament — a constitutional requirement when Kenyan troops are to be sent abroad.

Lawmakers on Wednesday announced they would summon the country’s police chief Japhet Koome and Interior Minister Kithure Kindiki for clarity about the mission, which some legal experts suggest is unconstitutional.

President William Ruto said it was a “mission for humanity” in a nation ravaged by colonialism, while Foreign Minister Alfred Mutua said Kenya was doing “God’s will” by helping the descendants of African slaves in Haiti.

Both pointed to Kenya’s long record of contributing to peacekeeping missions abroad.

Kenya’s security forces — mainly military but also police — have deployed all over the world but the Haiti mission is “unusually risky”, said Murithi Mutiga, programme director for Africa at the International Crisis Group.

“The security challenges in Haiti are quite different, where you have gangs operating in densely populated, low-income settlements, with very good knowledge of the terrain, and a commercial interest in maintaining that control,” he told AFP.

“It is an unusual intervention, it is one that Kenya has not done before, and I think they need to be very deliberate and careful.”

– ‘Suicide mission’ –

Koome says his men are “well trained” and the Haiti contingent will be drawn from specialised units.

The deployment — initially approved for one year — envisions Kenyan police on the offensive with their Haitian counterparts, who are outnumbered and outgunned by gang members.

But Tonui said Kenya’s police were mostly trained in light weapons and had little combat experience, suffering casualties at home against poorly-armed bandits and cattle rustlers.

“The fighters in Haiti have 0.50 calibre, which is a real heavy machine gun,” said Tonui from the Nairobi-based organisation Kenya Veterans for Peace.

“Our policemen are not trained like the military in map reading. They are not trained in communication. They are not trained in handling weapons like machine guns.”

Ekuru Aukot, an opposition politician and lawyer who helped draft Kenya’s revised constitution, put it more bluntly.

“That deployment is a suicide mission for our 1000 police officers,” he posted on X, formerly called Twitter.

– ‘Kenyan blood’ –

Some of Ruto’s opponents have cast the intervention as naive and accused the government of risking police lives in the pursuit of international gratitude.

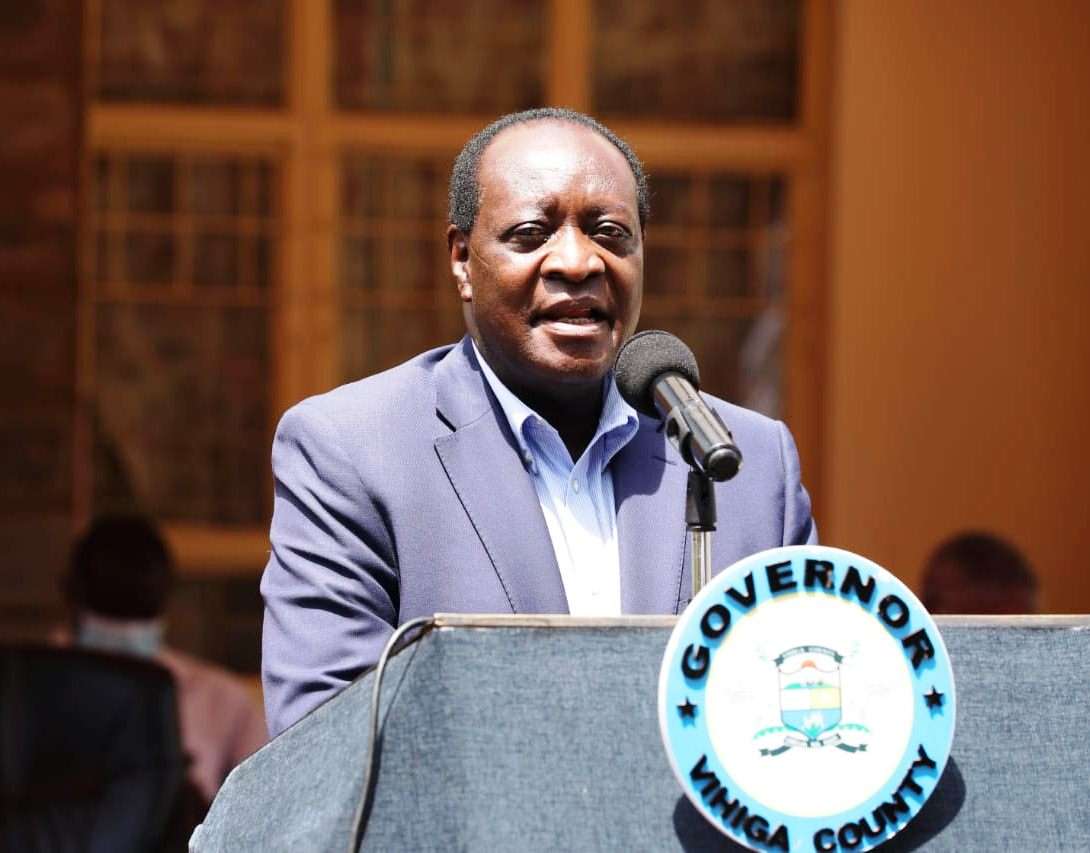

“We are not going to accept using Kenyan blood to fight on the doorstep of the United States of America, one of the most powerful nations in the world, just to please our president,” said Ruto critic James Orengo, governor of the western county of Siaya.

Mutiga said the tortured history of foreign misadventures in Haiti meant Kenya risked being seen as meddling to shore up a weak government.

Washington “spotted an opportunity to encourage the Kenyans to take the lead on this” but Nairobi was also keen to appear as “an actor that can contribute to peacebuilding”, he added.

On a visit to Nairobi last month, Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin said the US was working with Congress to provide $100 million in assistance for the mission, and urged other nations “to follow Kenya’s great example to step up”.

Rights watchdogs say Kenyan police have a history of using sometimes lethal force against civilians, and that they pose an unacceptable risk in Haiti where foreign troops have committed abuses in past interventions.

Mutua has brushed aside concerns that Kenya’s mission might be rushed or unwanted, saying internal polling indicated 80 per cent of Haitians welcomed their presence.